Novel quantifiable metrics for the identification of non-systemic small drugs

Miles Benardout, Stephen P. Wren, Adam Le Gresley, Amr ElShaer

Kingston University

Introduction

The drug design process requires a medicinal chemist to not only consider the properties of a compound that alter the therapeutic activity of a compound, but also the pharmacological properties of how a compound behaves in the body, commonly known as the properties affecting Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME). These ADME characteristic define the bioavailability of a given drug.

Typically, the majority drugs going to market are required to be orally bioavailable. This is often predicted in the early stage of the design process by well-known ‘rule of thumb’ approaches, such as Lipinski’s rule of 5 criteria (1), and later filters such as the Veber, Ghose, and Muegge filters (2–4). Although they are useful methods for the identification of orally bioavailable compounds, over-reliance on these filters has led to an over-restriction of chemical space for small molecules, and although fairly accurate for identifying orally bioavailable compounds, they are notably weaker at accurately identifying compounds with poor oral bioavailability (5).

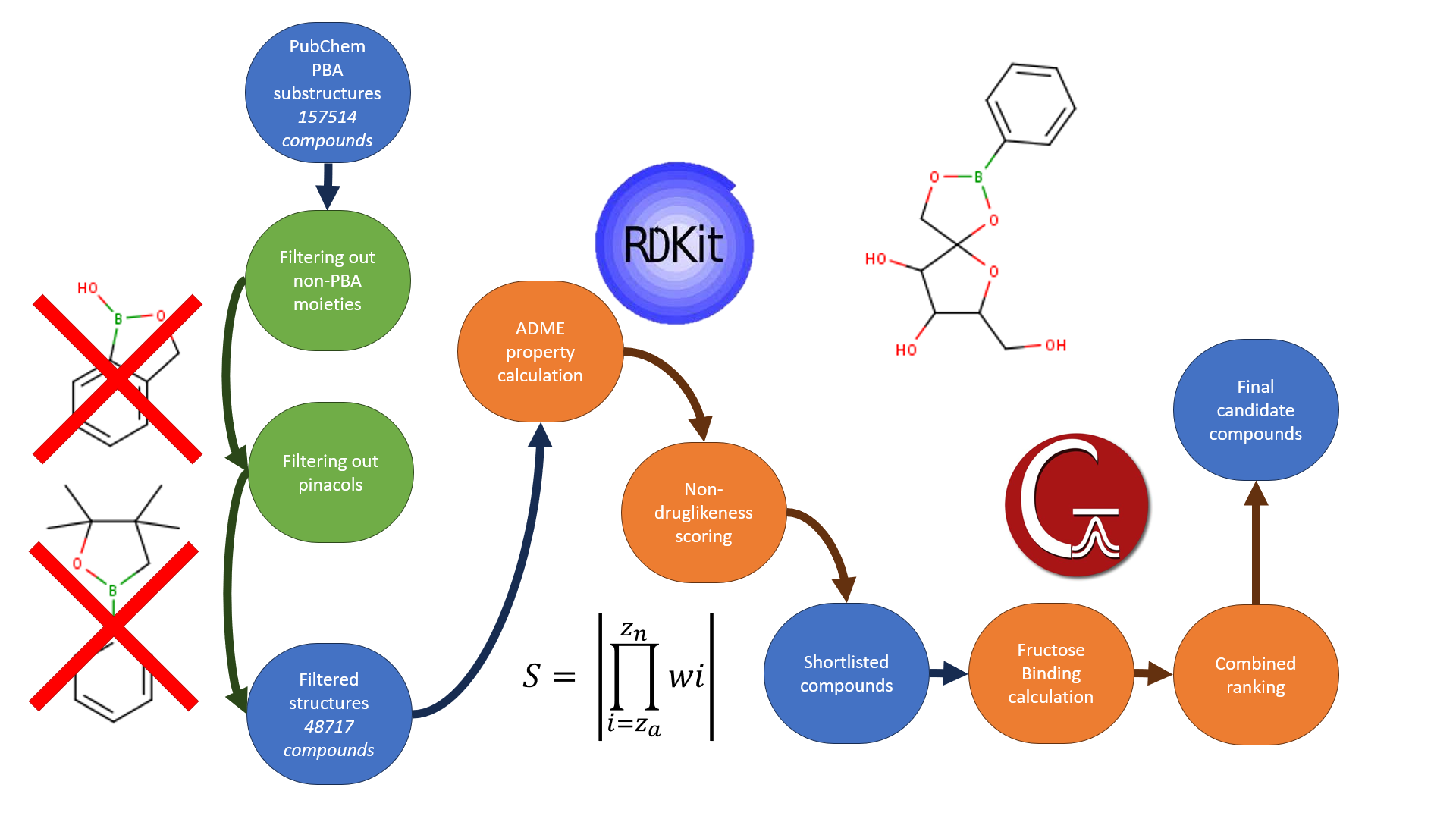

Our goal was to develop a quantifiable metric to identify pre-existing compounds with a high likelihood of poor oral bioavailability, in order to create a library of small molecules with high gut residence. Please see below a diagram describing our workflow for the project as a whole to identify potential non-systemic fructose scavengers.

Fructose Malabsorption

The goal of our discovery of non-systemic drugs is to identify suitable candidates for the treatment of Fructose Malabsorption, a condition related to the body’s inability to absorb an excess of fructose in the small intestine, leading to symptoms commonly associated with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. It is known that the phenylboronic acid functional group is able to bind to fructose, and we aim to develop a library of non-systemic fructose scavengers for the treatment of fructose malabsorption. Current treatments for fructose malabsorption are typically preventative, and primarily consist of dietary interventions; however, there is room for novel medicinal intervention in the treatment of fructose malabsorption.

Data mining

In order to create our library of candidate fructose scavengers, we focused on pre-existing phenylboronic acids found in the literature, as listed by freely available compound libraries. As an initial proof of concept for our scoring function, compound data will be exclusively derived from PubChem (6). A substructure search for phenylboronic acid (SMILES: OB(O)C1=CC=CC=C1 ) yielded at total of 220284 compounds for initial analysis. Since we are aiming to identify small molecules that we predict to have a high gut residence, we limited the maximum molecular weight to 700, resulting in a total of 157,514 compounds.

Initial compound filtering and processing

As with any data set, the data must be pre-processed prior to analysis, to ensure the quality of analysis (“garbage in, garbage out”). In our case, the dataset containing, in addition to the phenyl boronic acid compounds we want to analyse, a number of benzoboxoroles, and pinacol-protected compounds. After filtering out these unwanted compounds, we were left with 48717 compounds for evaluation.

Selection and calculation of Physiochemical descriptors

In order to predict non-druglikess in the longlist of compounds, we needed a consistent method of calculating the physiochemical (ADME) descriptors for each compound. Using RDKit (7), a free and open source cheminformatics library for the Python programming language, we were able to calculate descriptors in bulk for all compounds. Although we aim to design a metric that is inherently modular in nature, enabling the incorporation of any additional descriptors, we chose to select descriptors that we felt confident in describing their effect on oral bioavailability.

These include:

- Lipophilicity (logP) (8)

- Molar Refractivity (MR) (8)

- Topological Polar Surface Area (TPSA)

- Molecular weight (MW)

- Number of rotatable bonds (RotB)

- Number of Hydrogen bond donors (HBD)

- Number of Hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA)

- Fraction of Carbon atoms that are sp3 hybridised (FSP3) (9)

Once calculated, it was important to consider that all these descriptors have different scales, and in order to equally weight each descriptor for relative comparison, each value must be normalised in a way that gives greater value to raw values that may indicate poor druglikeness. For MR, TPSA, MW, RotB, HBD and HBA, higher values will indicate poor oral bioavailability; for FSP3, lower values indicate poor oral bioavailability, and for logP, increasing distance from the mean logP (i.e. Extreme values higher or lower than the mean) will indicate poor oral bioavailability. By taking into account these criteria, and the mean and standard deviation for each descriptor, normalised values for each descriptor were obtained.

The scoring function

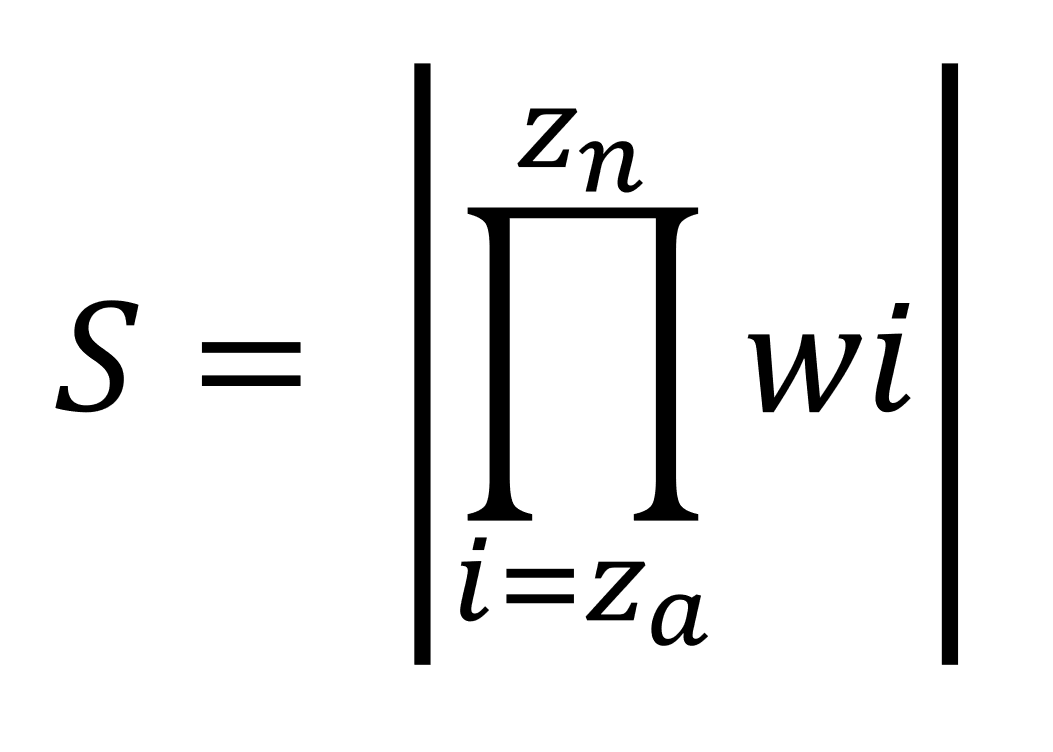

The scoring function used to identify non-systemic drugs is shown below

Where:

- S = score (higher = less druglike)

- Za = normalised descriptor value

- W = weighting (in the case of this proof-of-conception, always equals one)

Higher scores indicate the least druglike compounds in the dataset, and thus the most desirable for our application as fructose scavengers.

Results

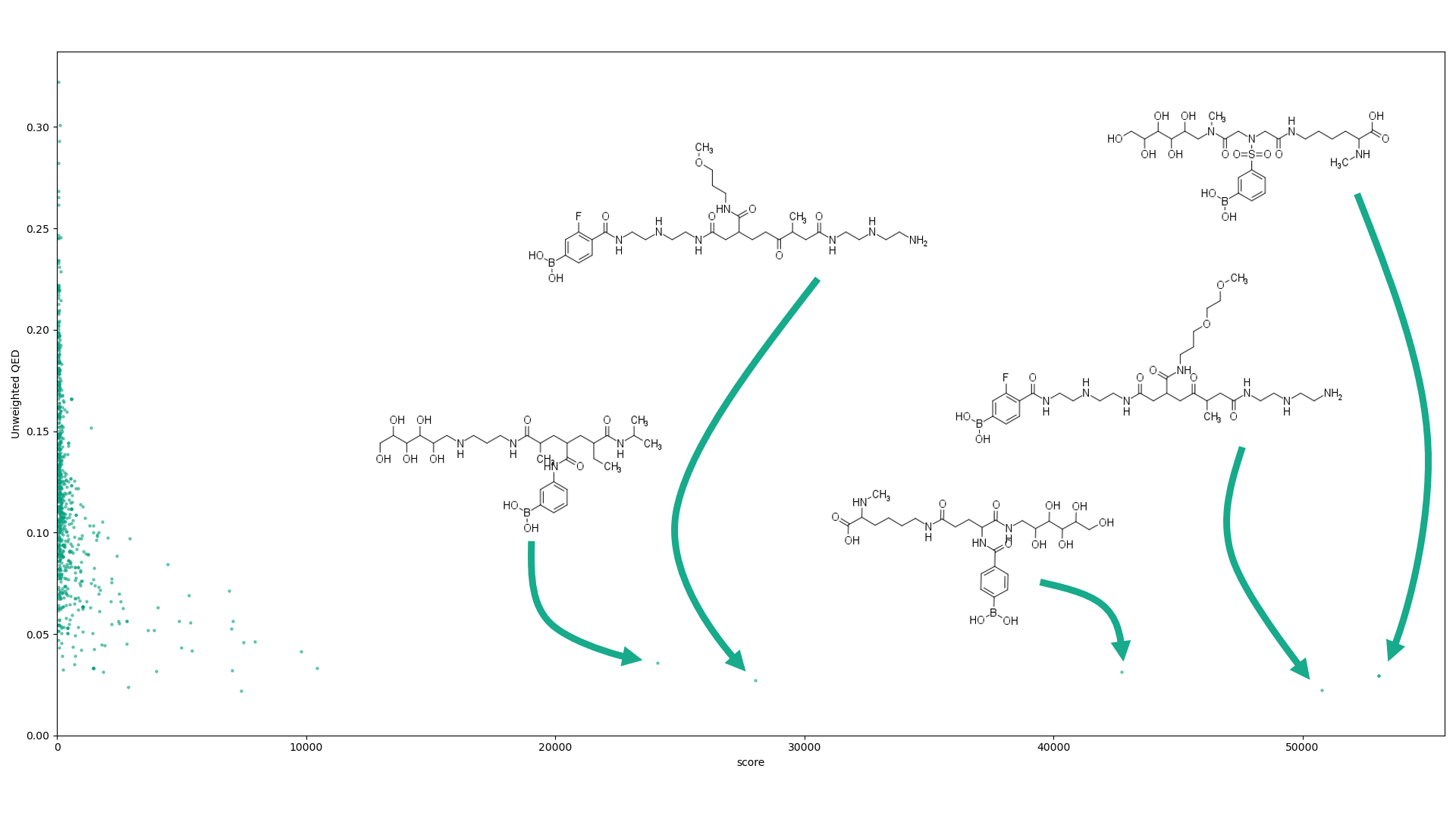

Using Bickerton’s Quantitative Estimate of Druglikeness (QED) score for comparison (10), we present the results of our scoring function below, with some of the highest scoring, and therefore least druglike, compounds labelled.

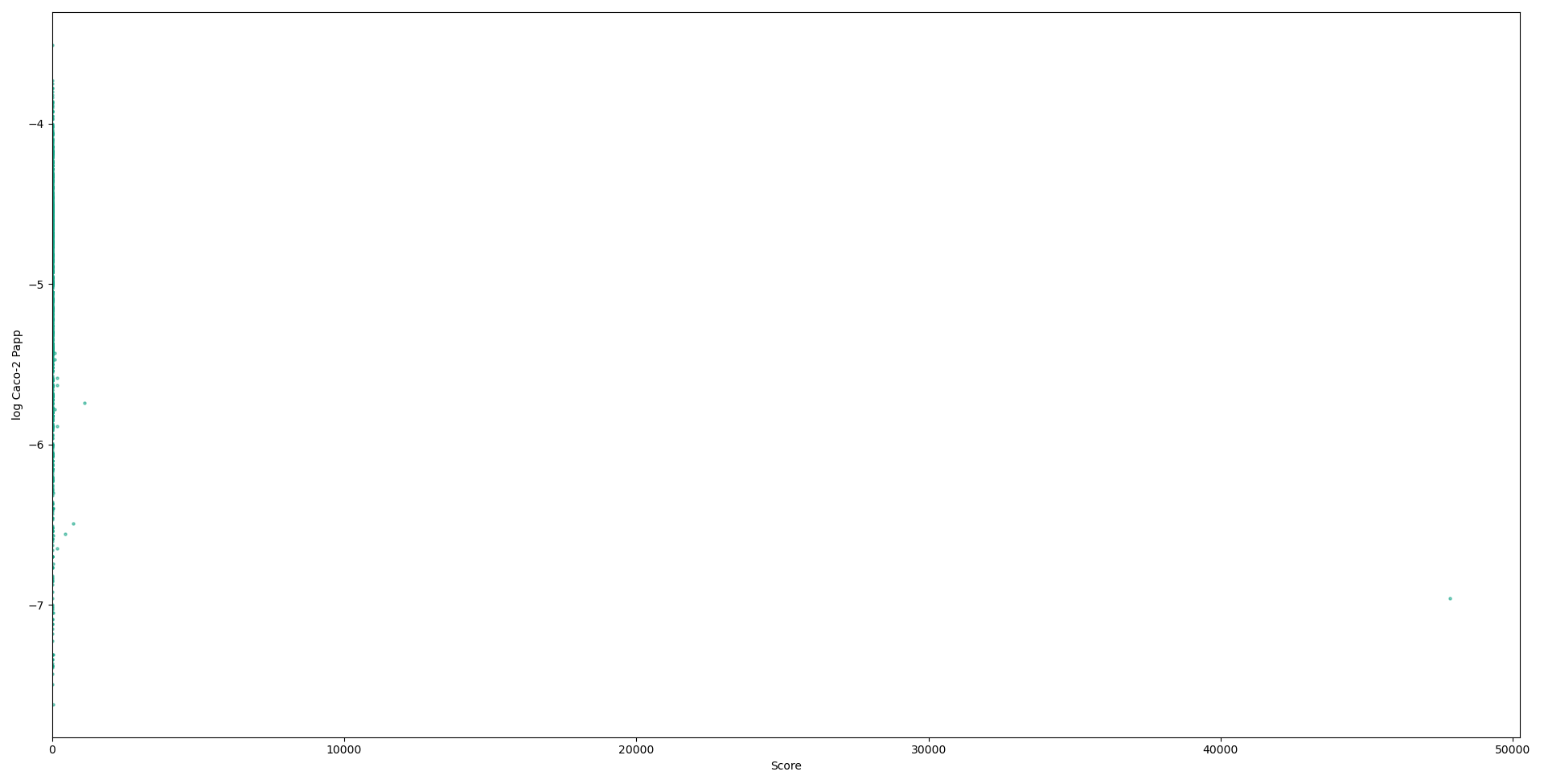

Although there is a high v variance in the QED value for the lower scoring compounds, the variance decreases and trends to a negative correlation between our score and QED, indicating its potential for the identification of non-systemic compounds. We also calculated scores for a dataset containing known caco-2 papp results, a commonly-used in vitro cell line assay for the prediction of drug absorption through the small intestine. There are 1017 compounds in this dataset (11), significantly lower than the larger dataset from PubChem used primarily, meaning although it’s important to not draw complete conclusions from this more limited dataset, it was promising to see a similar trend showing, where high scores correlated with low caco-2 papp values.

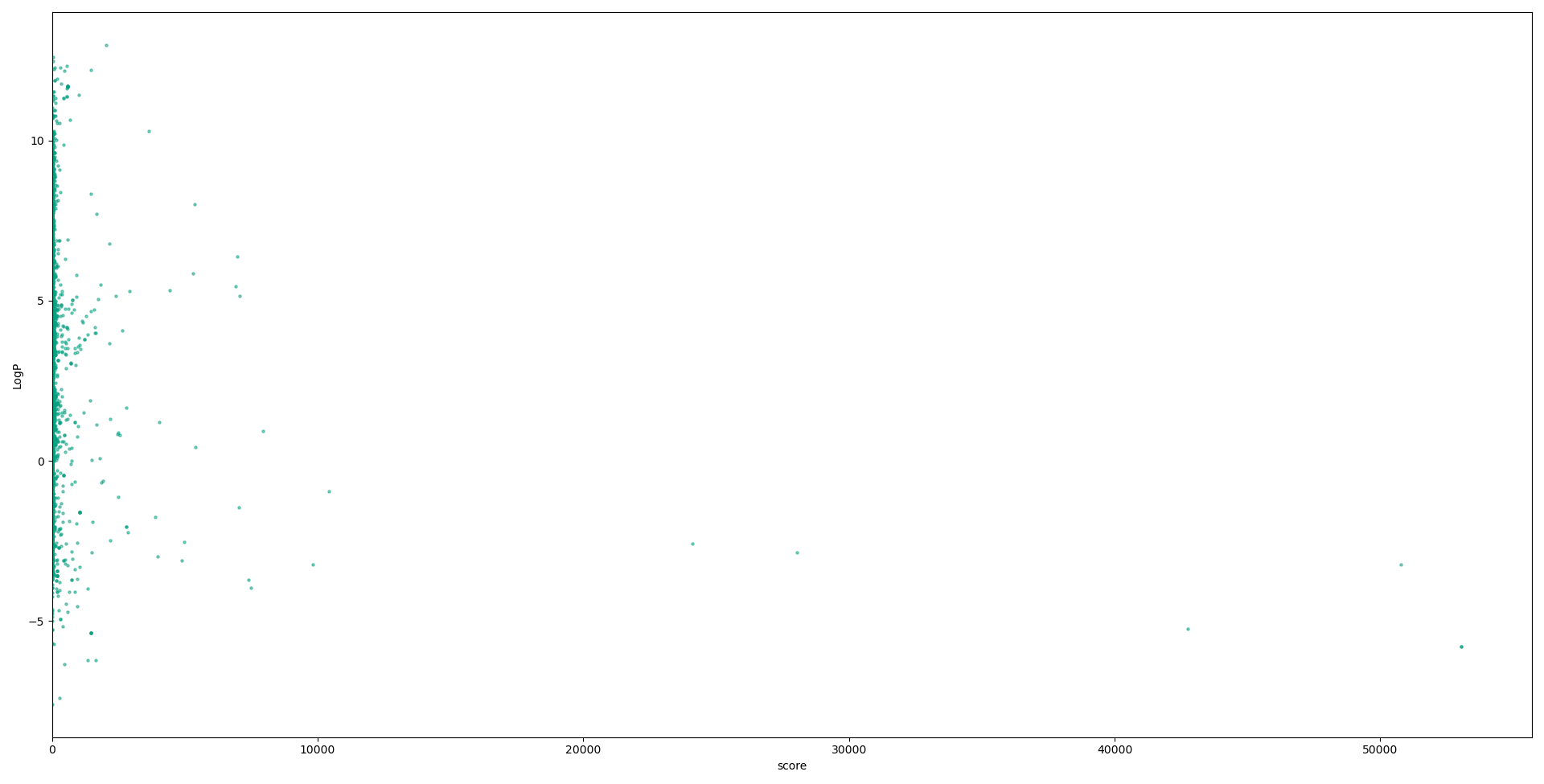

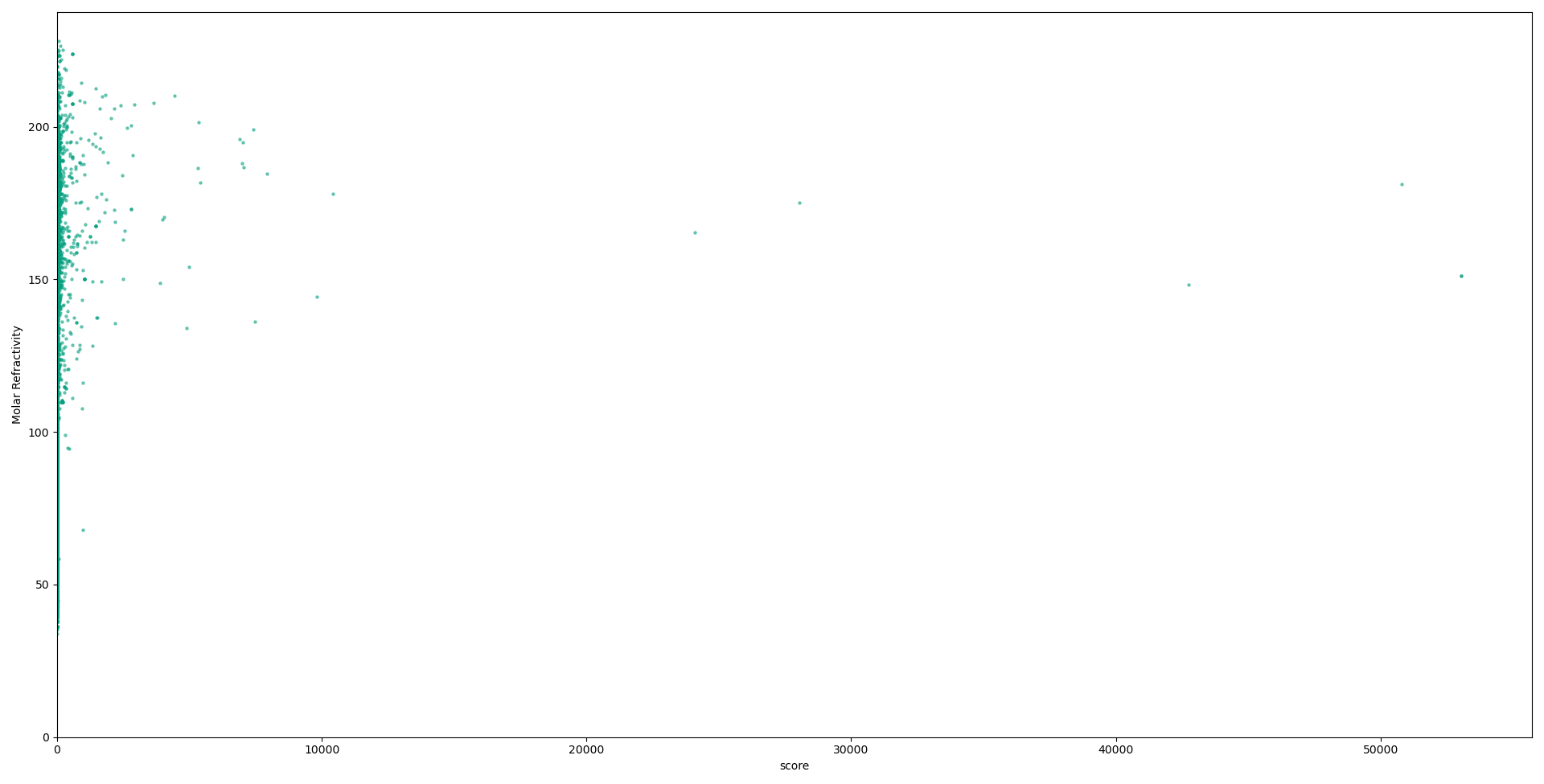

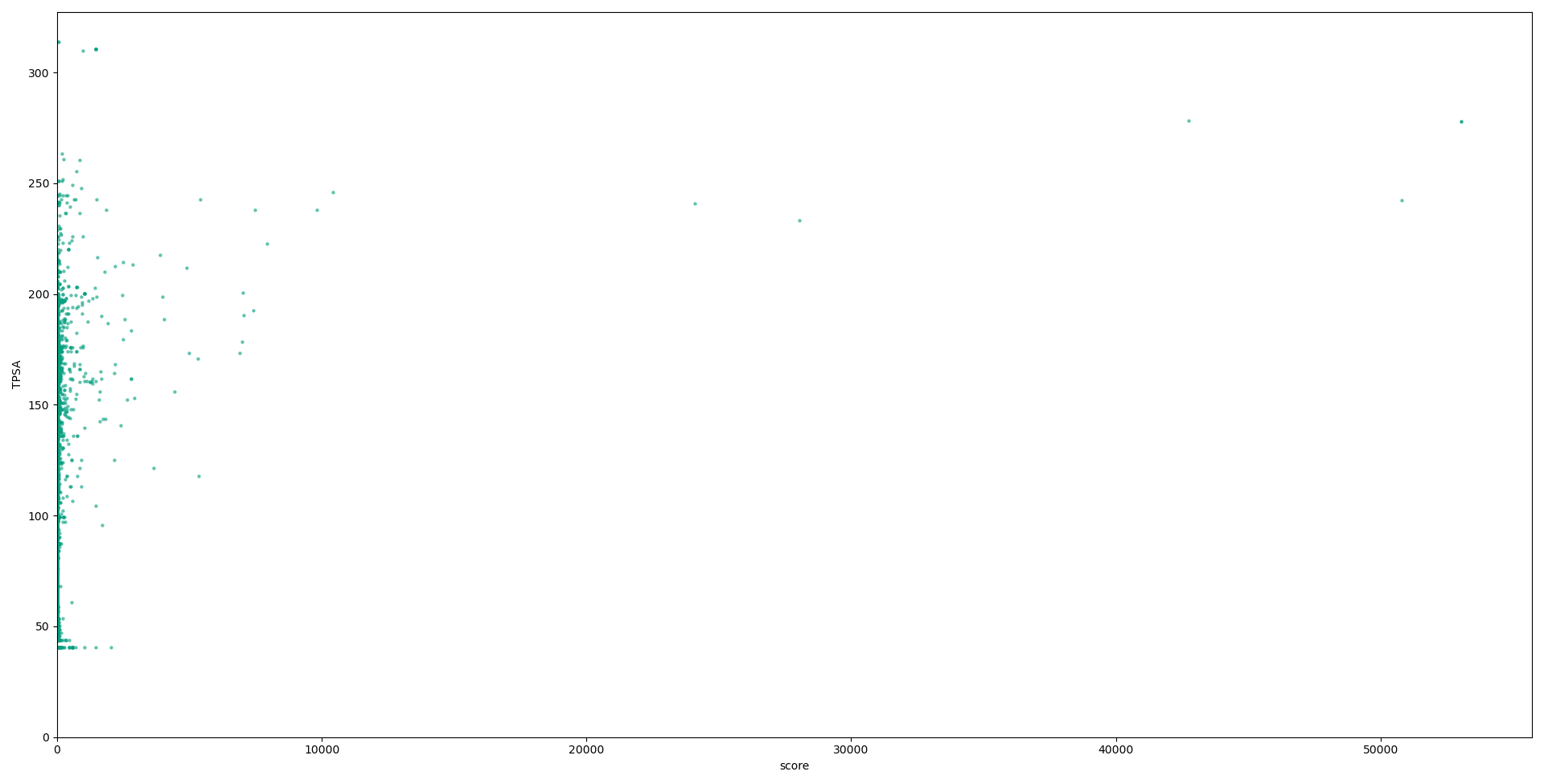

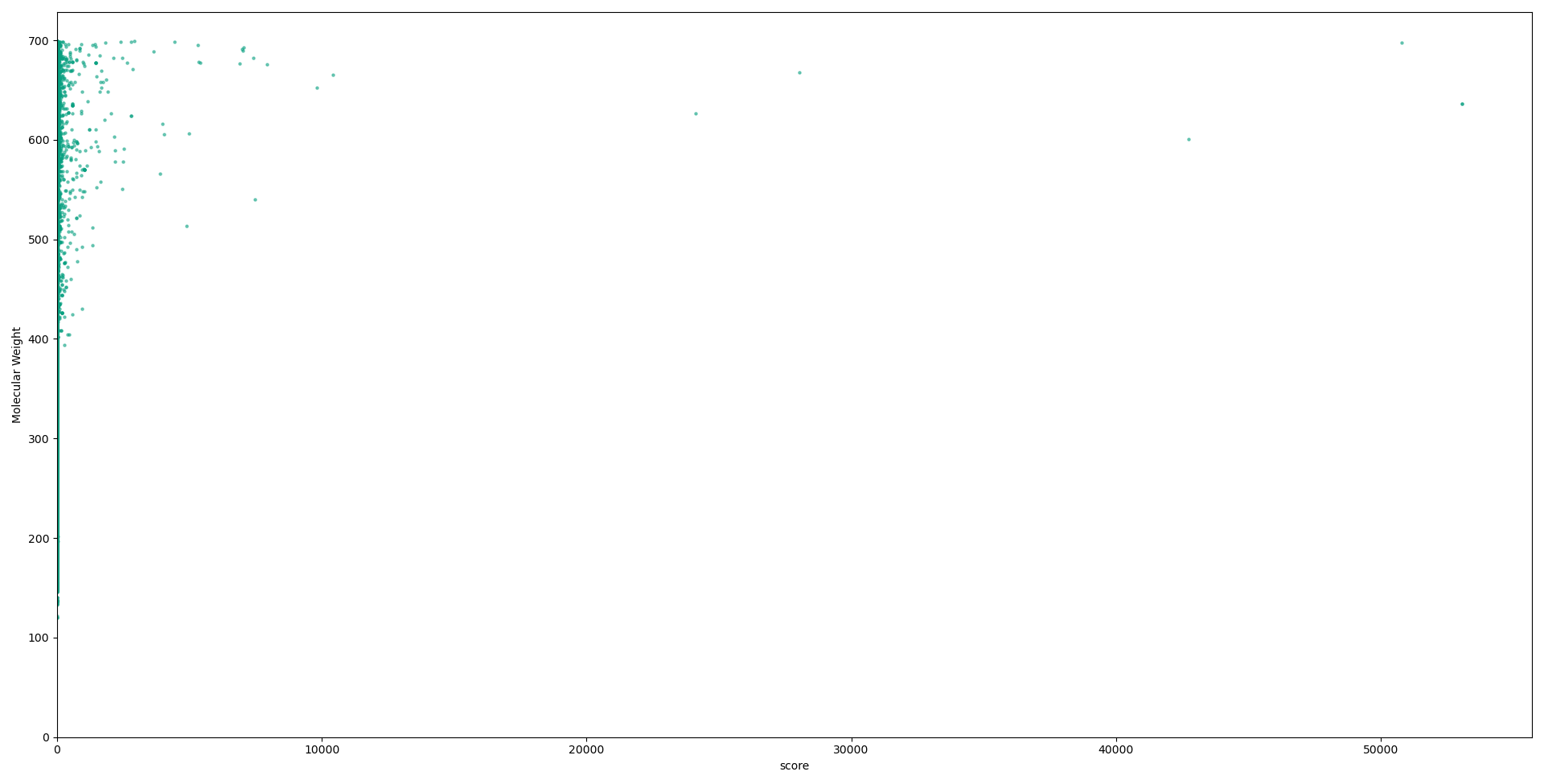

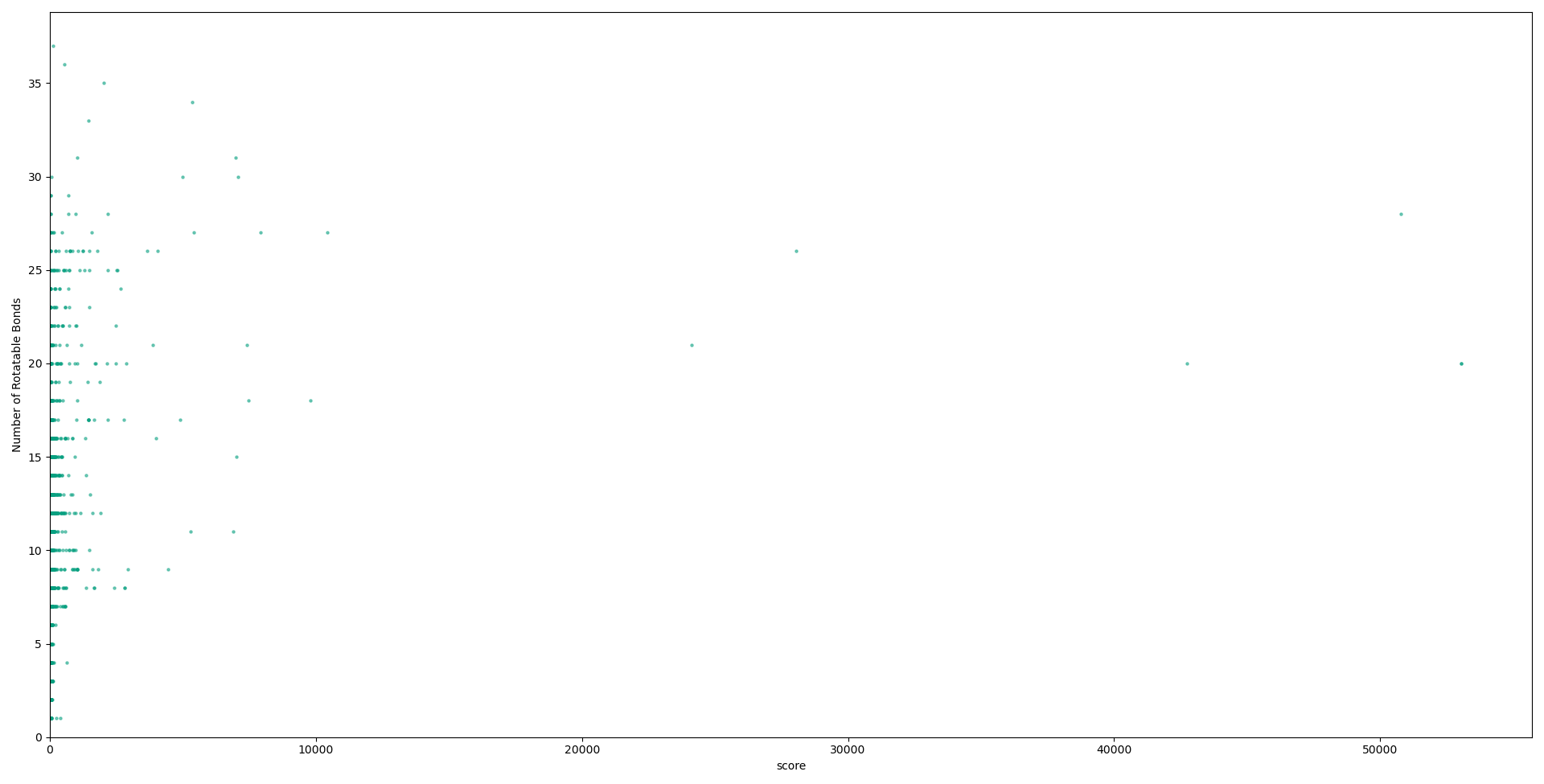

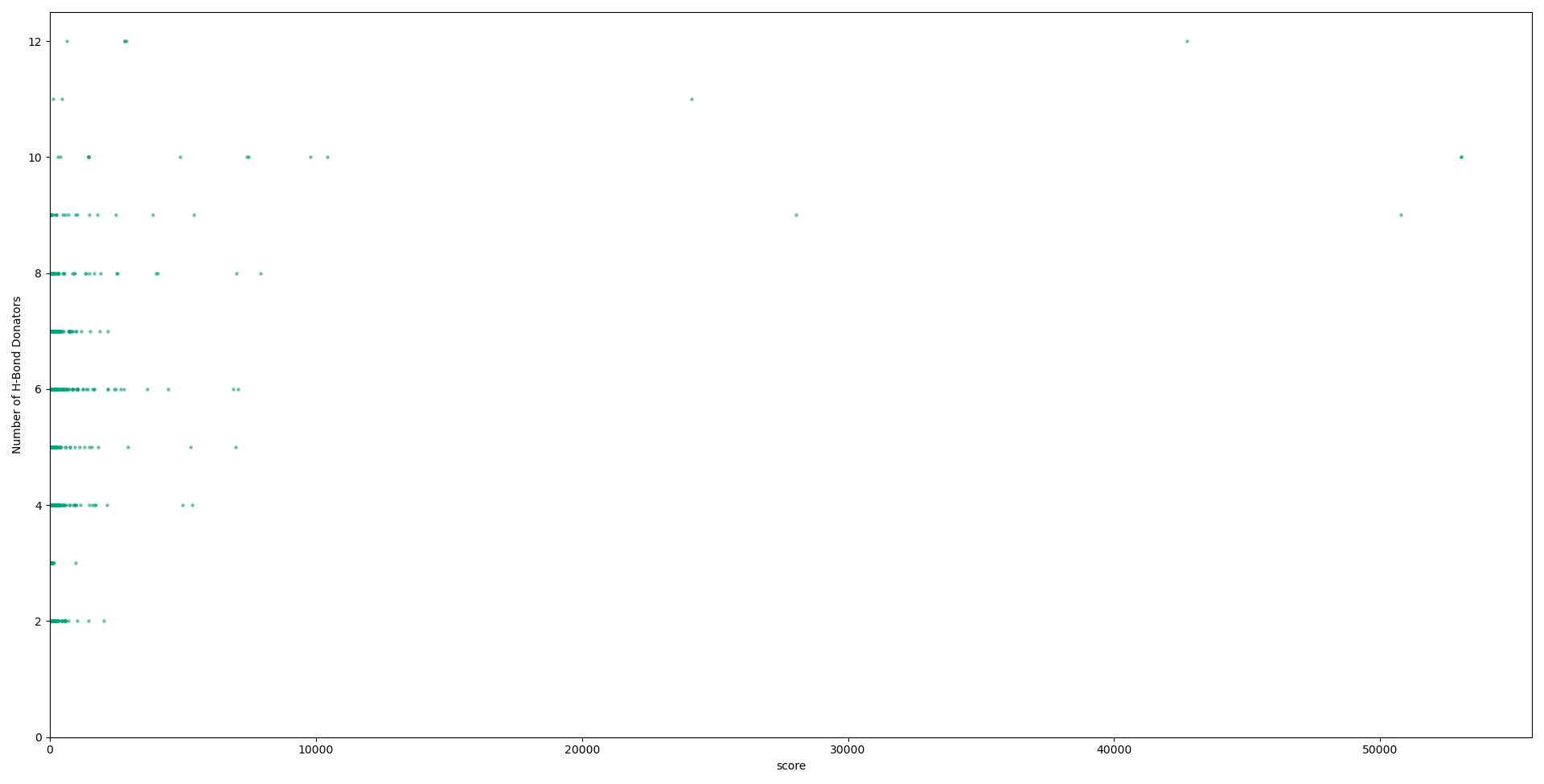

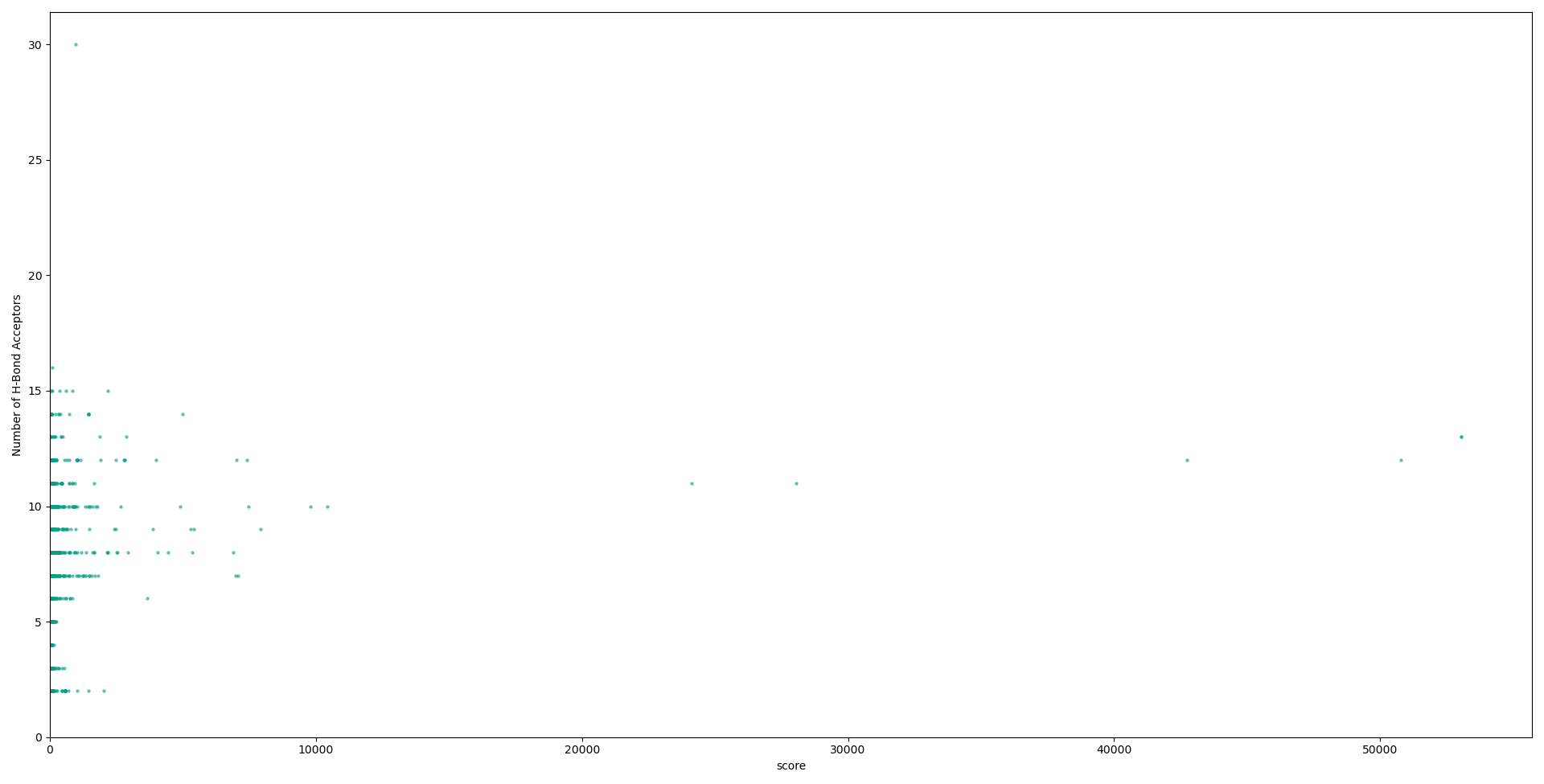

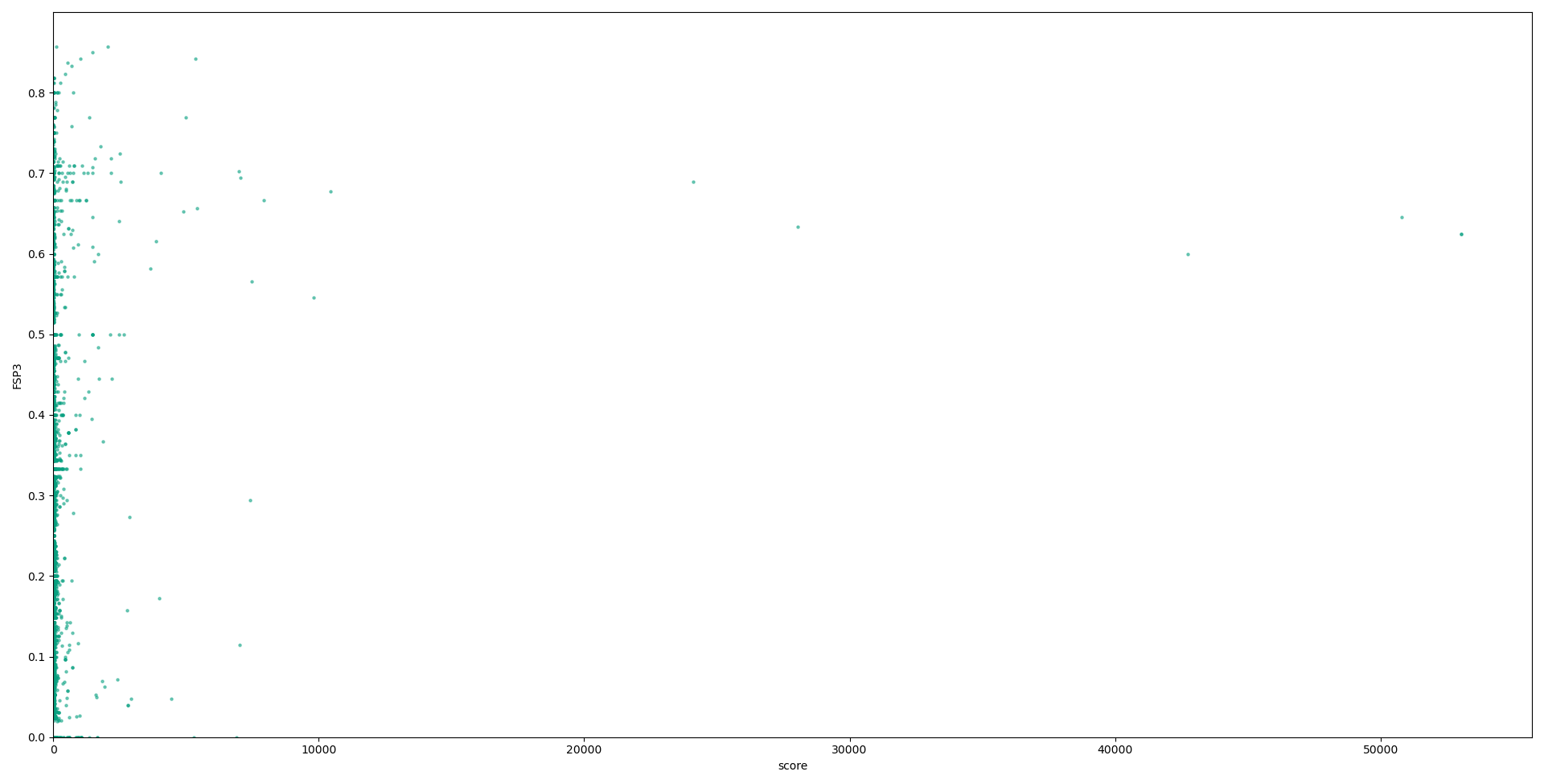

Below we have graphs describing the relationship between each descriptor used in our calculations, and the scores for each compound. Although no solid conclusion can be made from these graphs, they help to highlight the need for more holistic approaches to designing metrics to evaluate druglikess, and the need to move on from “black-and-white” druglikess filters.

Conclusions and future work

We have developed a promising metric for the identification of non-druglike small molecules. Following on from this work, we will take a subset of compounds from these results with the highest scores (i.e. least druglike). We intend to undertake in silico thermodynamic calculations of these compounds to evaluate their affinity and selectivity in fructose binding. Combining those results, and the results presented today, we aim to generate a shortlist of compounds we believe have high potential as non-systemic, fructose selective scavengers.

We have also formed a collaborative project to investigate the application of neural networks in order to optimise this metric’s ability to predict caco-2 papp permeability, in order to maximise this metrics ability to identify non-systemic small molecules.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is sugar transport important? Sugar transport is crucial for the successful absorption of monosaccharides from the small intestine into the bloodstream. Requiring the utilisation of specialised channel proteins for their absorption, high concentrations of fructose in the small intestine can cause these channel proteins to become overloaded, in particular when fructose is present in excess of glucose, resulting in the onset of gastrointestinal complaints.

What is absorption/permeability? Drug absorption is the process of a drug passing through the gastrointestinal membrane in order to enter the bloodstream. Most oral drugs need to permeate the small intestine to be distributed to their target via the bloodstream. However, the target of non-systemic drugs are located within the gastrointestinal lumen itself, so the drugs need to be designed in order to limit absorption as much as possible.

what are boronates/boronic acids? Boronic acids are a functional group with a boron atom connected to two hydroxyl groups and an alkyl/aryl group. Well known for their use as part of the Suzuki coupling reaction, they have also been used in medicinal applications.

What is PBA? PBA is shorthand for phenylboronic acid, the base for the compounds we are trying to identify, as phenylboronic acids have been noted for their ability to bind to 1,2-cis diols, such as those found in monosaccharides.

Why are computers needed for this work? They enable the rapid, high-throughput calculations of a huge number of compounds that simply could not be calculated in a reasonable time manually.

What will happen at the end of this study? We aim to propose a small set of compounds for synthesis, which we believe will have a high likelihood for success as non-system fructose selective scavengers. We aim to start a project in the future with a future PhD student to synthesise these compounds and evaluate them in vitro.

References

- Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Vol. 23, Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. Elsevier Science B.V.; 1997. p. 3–25.

- Veber DF, Johnson SR, Cheng HY, Smith BR, Ward KW, Kopple KD. Molecular Properties That Influence the Oral Bioavailability of Drug Candidates. J Med Chem. 2002 Jun 1;45(12):2615–23. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1021/jm020017n

- Ghose AK, Viswanadhan VN, Wendoloski JJ. A Knowledge-Based Approach in Designing Combinatorial or Medicinal Chemistry Libraries for Drug Discovery. 1. A Qualitative and Quantitative Characterization of Known Drug Databases. J Comb Chem. 1999 Jan 12;1(1):55–68. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1021/cc9800071

- Muegge I, Heald SL, Brittelli D. Simple Selection Criteria for Drug-like Chemical Matter. J Med Chem. 2001 Jun 1;44(12):1841–6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1021/jm015507e

- Benet LZ, Hosey CM, Ursu O, Oprea TI. BDDCS, the Rule of 5 and Drugability. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016 Jun 6 101:89. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC4910824/

- Kim S, Chen J, Cheng T, Gindulyte A, He J, He S, et al. PubChem 2023 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023 Jan 6;51(D1):D1373–80. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac956

- RDKit: Open-source cheminformatics. https://www.rdkit.org.

- Wildman SA, Crippen GM. Prediction of Physicochemical Parameters by Atomic Contributions. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 1999 Sep 27;39(5):868–73. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1021/ci990307l

- Lovering F, Bikker J, Humblet C. Escape from Flatland: Increasing Saturation as an Approach to Improving Clinical Success. J Med Chem. 2009 Nov 12;52(21):6752–6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1021/jm901241e

- Bickerton GR, Paolini G V., Besnard J, Muresan S, Hopkins AL. Quantifying the chemical beauty of drugs. Nat Chem. 2012 Feb;4(2):90. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC3524573/

- Wang NN, Dong J, Deng YH, Zhu MF, Wen M, Yao ZJ, et al. ADME Properties Evaluation in Drug Discovery: Prediction of Caco-2 Cell Permeability Using a Combination of NSGA-II and Boosting. J Chem Inf Model. 2016 Apr 25;56(4):763–73. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00642